A selection of the most important recent news, articles, and papers about quantum computing.

News, Articles, and Analyses

Infleqtion Leads the Way with First Quantum Computer Installation at NQCC — Infleqtion

(Tuesday, July 16, 2024) “We’re thrilled to announce the installation of our state-of-the-art neutral atom quantum computer at the National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC). As the first company to deploy hardware under the NQCC’s quantum computing testbed programme, this milestone showcases our cutting-edge technology and de”

Oxford company unveils ‘pivotal’ quantum computing chip – BBC News

(Tuesday, July 16, 2024) “Oxford Ionics claim to have created the first quantum chip of its kind that could be mass-produced.”

Pritzker announces federal partner for quantum computing campus

(Wednesday, July 17, 2024) “CHICAGO (WCIA) — Illinois’ proposal to create a new quantum computing campus has a new partner with a federal agency. Governor J.B. Pritzker announced the partnership of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, part of the U.S. Department of Defense, with Illinois’ quantum computing campus Tuesday. The partnership is named Quantum Proving Ground. “The future of […]”

Technical Papers and Preprints

[2107.02151] Continuous Variable Quantum Algorithms: an Introduction

Authors: Buck, Samantha; Coleman, Robin; Sargsyan, Hayk

(Monday, July 05, 2021) “Quantum computing is usually associated with discrete quantum states and physical quantities possessing discrete eigenvalue spectrum. However, quantum computing in general is any computation accomplished by the exploitation of quantum properties of physical quantities, discrete or otherwise. It has been shown that physical quantities with continuous eigenvalue spectrum can be used for quantum computing as well. Currently, continuous variable quantum computing is a rapidly developing field both theoretically and experimentally. In this pedagogical introduction we present the basic theoretical concepts behind it and the tools for algorithm development. The paper targets readers with discrete quantum computing background, who are new to continuous variable quantum computing.”

(Monday, July 05, 2021) “Quantum computing is usually associated with discrete quantum states and physical quantities possessing discrete eigenvalue spectrum. However, quantum computing in general is any computation accomplished by the exploitation of quantum properties of physical quantities, discrete or otherwise. It has been shown that physical quantities with continuous eigenvalue spectrum can be used for quantum computing as well. Currently, continuous variable quantum computing is a rapidly developing field both theoretically and experimentally. In this pedagogical introduction we present the basic theoretical concepts behind it and the tools for algorithm development. The paper targets readers with discrete quantum computing background, who are new to continuous variable quantum computing.”

Towards quantum enhanced adversarial robustness in machine learning | Nature Machine Intelligence

(Thursday, May 25, 2023) “To fulfil the potential of quantum machine learning for practical applications in the near future, it needs to be robust against adversarial attacks. West and colleagues give an overview of recent developments in quantum adversarial machine learning, and outline key challenges and future research directions to advance the field.”

[2407.02467] Error mitigation with stabilized noise in superconducting quantum processors

Authors: Kim, Youngseok; Govia, Luke C. G.; Dane, Andrew; Berg, Ewout van den; Zajac, David M.; Mitchell, Bradley; Liu, Yinyu; Balakrishnan, Karthik; Keefe, George; Stabile, Adam; Pritchett, Emily; Stehlik, Jiri; Kandala, Abhinav

(Tuesday, July 02, 2024) “Pre-fault tolerant quantum computers have already demonstrated the ability to estimate observable values accurately, at a scale beyond brute-force classical computation. This has been enabled by error mitigation techniques that often rely on a representative model on the device noise. However, learning and maintaining these models is complicated by fluctuations in the noise over unpredictable time scales, for instance, arising from resonant interactions between superconducting qubits and defect two-level systems (TLS). Such interactions affect the stability and uniformity of device performance as a whole, but also affect the noise model accuracy, leading to incorrect observable estimation. Here, we experimentally demonstrate that tuning of the qubit-TLS interactions helps reduce noise instabilities and consequently enables more reliable error-mitigation performance. These experiments provide a controlled platform for studying the performance of error mitigation in the presence of quasi-static noise. We anticipate that the capabilities introduced here will be crucial for the exploration of quantum applications on solid-state processors at non-trivial scales.”

(Tuesday, July 02, 2024) “Pre-fault tolerant quantum computers have already demonstrated the ability to estimate observable values accurately, at a scale beyond brute-force classical computation. This has been enabled by error mitigation techniques that often rely on a representative model on the device noise. However, learning and maintaining these models is complicated by fluctuations in the noise over unpredictable time scales, for instance, arising from resonant interactions between superconducting qubits and defect two-level systems (TLS). Such interactions affect the stability and uniformity of device performance as a whole, but also affect the noise model accuracy, leading to incorrect observable estimation. Here, we experimentally demonstrate that tuning of the qubit-TLS interactions helps reduce noise instabilities and consequently enables more reliable error-mitigation performance. These experiments provide a controlled platform for studying the performance of error mitigation in the presence of quasi-static noise. We anticipate that the capabilities introduced here will be crucial for the exploration of quantum applications on solid-state processors at non-trivial scales.”

[2407.05178] A typology of quantum algorithms

Authors: Arnault, Pablo; Arrighi, Pablo; Herbert, Steven; Kasnetsi, Evi; Li, Tianyi

(Saturday, July 06, 2024) “We draw the current landscape of quantum algorithms, by classifying about 130 quantum algorithms, according to the fundamental mathematical problems they solve, their real-world applications, the main subroutines they employ, and several other relevant criteria. The primary objectives include revealing trends of algorithms, identifying promising fields for implementations in the NISQ era, and identifying the key algorithmic primitives that power quantum advantage.”

(Saturday, July 06, 2024) “We draw the current landscape of quantum algorithms, by classifying about 130 quantum algorithms, according to the fundamental mathematical problems they solve, their real-world applications, the main subroutines they employ, and several other relevant criteria. The primary objectives include revealing trends of algorithms, identifying promising fields for implementations in the NISQ era, and identifying the key algorithmic primitives that power quantum advantage.”

Share this:

Availability of my book Dancing with Python and its table of contents

My new book Dancing with Python: Learn Python software development from scratch and get started with quantum computing is now available for purchase from Amazon and Packt Publishing.

Develop skills in Python by implementing exciting algorithms, including mathematical functions, classical searching, data analysis, plotting data, machine learning techniques, and quantum circuits.

Key Features

Learn Python basics to write elegant and efficient code

Create quantum circuits and algorithms using Qiskit and run them on quantum computing hardware and simulators

Delve into Python’s advanced features, including machine learning, analyzing data, and searching

Contributors

About the author

About the reviewer

Contents

List of Figures

Preface

Why did I write this book?

For whom did I write this book?

What does this book cover?

What conventions do I use in this book?

Get in touch

1 Doing the Things That Coders Do

1.1 Data

1.2 Expressions

1.3 Functions

1.4 Libraries

1.5 Collections

1.6 Conditional processing

1.7 Loops

1.8 Exceptions

1.9 Records

10 Contents

1.10 Objects and classes

1.11 Qubits

1.12 Circuits

1.13 Summary

I Getting to Know Python

2 Working with Expressions

2.1 Numbers

2.2 Strings

2.3 Lists

2.4 Variables and assignment

2.5 True and False

2.6 Arithmetic

2.7 String operations

2.8 List operations

2.9 Printing

2.10 Conditionals

2.11 Loops

2.12 Functions

2.13 Summary

3 Collecting Things Together

3.1 The big three

3.2 Lists

3.3 The joy of O(1)

3.4 Tuples

3.5 Comprehensions

3.6 What does “Pythonic” mean?

3.7 Nested comprehensions

3.8 Parallel traverse

3.9 Dictionaries

3.10 Sets

3.11 Summary

4 Stringing You Along

4.1 Single, double, and triple quotes

4.2 Testing for substrings

4.3 Accessing characters

4.4 Creating strings

4.5 Strings and iterations

4.6 Strings and slicing

4.7 String tests

4.8 Splitting and stripping

4.9 Summary

5 Computing and Calculating

5.1 Using Python modules

5.2 Integers

5.3 Floating-point numbers

5.4 Rational numbers

5.5 Complex numbers

5.6 Symbolic computation

5.7 Random numbers

5.8 Quantum randomness

5.9 Summary

6 Defining and Using Functions

6.1 The basic form

6.2 Parameters and arguments

6.3 Naming conventions

6.4 Return values

6.5 Keyword arguments

6.6 Default argument values

6.7 Formatting conventions

6.8 Nested functions

6.9 Variable scope

6.10 Functions are objects

6.11 Anonymous functions

6.12 Recursion

6.13 Summary

7 Organizing Objects into Classes

7.1 Objects

7.2 Classes, methods, and variables

7.3 Object representation

7.4 Magic methods

7.5 Attributes and properties

7.6 Naming conventions and encapsulation

7.7 Commenting Python code

7.8 Documenting Python code

7.9 Enumerations

7.10 More polynomial magic

7.11 Class variables

7.12 Class and static methods

7.13 Inheritance

7.14 Iterators

7.15 Generators

7.16 Objects in collections

7.17 Creating modules

7.18 Summary

8 Working with Files

8.1 Paths and the file system

8.2 Moving around the file system

8.3 Creating and removing directories

8.4 Lists of files and folders

8.5 Names and locations

8.6 Types of files

8.7 Reading and writing files

8.8 Saving and restoring data

8.9 Summary

II Algorithms and Circuits

9 Understanding Gates and Circuits

9.1 The software stack

9.2 Boolean operations and bit logic gates

9.3 Logic circuits

9.4 Simplifying bit expressions

9.5 Universality for bit gates

9.6 Quantum gates and operations

9.7 Quantum circuits

9.8 Universality for quantum gates

9.9 Summary

10 Optimizing and Testing Your Code

10.1 Testing your code

10.2 Timing how long your code takes to run

10.3 Optimizing your code

10.4 Looking for orphan code

10.5 Defining and using decorators

10.6 Summary

11 Searching for the Quantum Improvement

11.1 Classical searching

11.2 Quantum searching via Grover

11.3 Oracles

11.4 Inversion about the mean

11.5 Amplitude amplification

11.6 Searching over two qubits

11.7 Summary

III Advanced Features and Libraries

12 Searching and Changing Text

12.1 Core string search and replace methods

12.2 Regular expressions

12.3 Introduction to Natural Language Processing

12.4 Summary

13 Creating Plots and Charts

13.1 Function plots

13.2 Bar charts

13.3 Histograms

13.4 Pie charts

13.5 Scatter plots

13.6 Moving to three dimensions

13.7 Summary

14 Analyzing Data

14.1 Statistics

14.2 Cats and commas

14.3 pandas DataFrames

14.4 Data cleaning

14.5 Statistics with pandas

14.6 Converting categorical data

14.7 Cats by gender in each locality

14.8 Are all tortoiseshell cats female?

14.9 Cats in trees and circles

14.10 Summary

15 Learning, Briefly

15.1 What is machine learning?

15.2 Cats again

15.3 Feature scaling

15.4 Feature selection and reduction

15.5 Clustering

15.6 Classification

15.7 Linear regression

15.8 Concepts of neural networks

15.9 Quantum machine learning

15.10 Summary

Appendices

A Tools

A.1 The operating system command line

A.2 Installing Python

A.3 Installing Python modules and packages

A.4 Installing a virtual environment

A.5 Installing the Python packages used in this book

A.6 The Python interpreter

A.7 IDLE

A.8 Visual Studio Code

A.9 Jupyter notebooks

A.10 Installing and setting up Qiskit

A.11 The IBM Quantum Composer and Lab

A.12 Linting

B Staying Current

B.1 python.org

B.2 qiskit.org

B.3 Python expert sites

B.4 Asking questions and getting answers

C The Complete UniPoly Class

D The Complete Guitar Class Hierarchy

E Notices

E.1 Photos, images, and diagrams

E.2 Data

E.3 Trademarks

E.4 Python 3 license

F Production Notes

References

Other Books You May Enjoy

Index

Index Formatting Examples

Python function, method, and property index

Python class index

Python module and package index

General index

Share this:

Call for papers: Education, Research, and Application of Quantum Computing – HICSS 2022

My IBM Quantum colleague Dr. Andrew Wack and I are hosting a minitrack at the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) 2022.

The description of the minitrack is:

There is no question that quantum computing will be a technology that will spur breakthroughs in natural science, AI, and computational algorithms such as those used in finance. IBM, Google, Honeywell, and several startups are working hard to create the next generation of “supercomputers” based on universal quantum technology.

What exactly is quantum computing, how does it work, how do we teach it, how do we leverage it in education and research, and what will it take to achieve these quantum breakthroughs?

The purpose of this minitrack is to bring together educators and researchers who are working to bring quantum computing into the mainstream.

We are looking for reports that

- improve our understanding of how to integrate quantum computing into business, machine learning, computer science, and applied mathematics university curriculums,

- describe hands-on student experiences with the open-source Qiskit quantum software development kit, and

- extend computational techniques for business, finance, and economics from classical to quantum systems.

It is part of the Decision Analytics and Service Science track at HICSS.

Please consider submitting a report and sharing this Call for Papers with your colleagues.

Share this:

The Amazon Kindle version of Dancing with Qubits is now available!

I’m pleased to announce that the Amazon Kindle version of my quantum computing book Dancing with Qubits is now available!

I’m pleased to announce that the Amazon Kindle version of my quantum computing book Dancing with Qubits is now available!

This book provides a comfortable and conversational introduction to quantum computing. I take you through the mathematics you need at a pace that allows you to understand not just “what” but also “why.” When we get to quantum computing, concepts like superposition and entanglement are shown to be natural ideas building on what we’ve already seen, and then illustrated via gates, circuits, and algorithms.

Throughout the book, I highlight important results, provide questions to answer, and give links to references where you can learn more. This allows the book to be used for self-study or as a textbook.

Important ideas like Quantum Volume are explained to give you a head start for reading more advanced texts and research papers. I provide many references to related content in math, physics, quantum computing, AI, and financial services. Dancing with Qubits concludes with questions for you to think about and ask experts so that you can gauge progress in the field over the next few years.

Features of the Kindle edition

- The text will get larger or smaller as you wish and you can change to a font that is comfortable for you to read.

- There are links throughout the book to other sections and the references in each chapter.

- Many of the references have links to external sources, such as arxiv or Nature for research papers.

- The content is in color, if your Kindle device supports it.

- You can search for terms throughout the book.

- I’ve maximized the number of mathematical expressions that are expressed textually (see below) to improve the reading experience.

The print version of Dancing with Qubits still has the full, rich mathematical formatting, albeit in black and white. In essence, whether you choose the print or Kindle version, the content is consistent and the formatting is the best I know how to produce for each medium.

Technical Notes

Here are a few comments about the production of the Kindle version, in case you are interested.

- The original content for Dancing with Qubits is in LaTeX. From that I can produce the black and white print version, a color PDF eBook, and an epub3 file from which the Amazon Kindle and several other MOBI eBook versions are created.

- I used make4ht and tex4ht to go from the LaTeX source files to HTML. While very powerful, the documentation is scarce and I spent many hours trying to figure how to make things work and then writing sed and Python scripts to fix things that were not quite right.

- I wrote Python scripts to create the various files needed for epub3, such as opf and navigation, and to break the 30,000+ line HTML file into smaller XHTML files. I used tidy several times to format the HTML and XHTML.

- The epub3 validators in several free epub3 editing apps either skipped problems entirely or gave false negatives. I found pagina EPUB-Checker to be the best software for validation.

- I wanted to maximize the amount of HTML formatting I could use and MathML is not available in a practical sense for all eBook formats. tex4ht produced very inconsistent results. So while I could express $x_2$ as x2 in the text without extra fonts, more two-dimensional objects like matrices had to be represented using images. I created macros to produce the right format based on what kind of document I was trying to produce.

- I used tikz/pgf and quantikz for the figures, especially the quantum circuit diagrams. I externalized the figures as JPEG images. It took quite a bit to figure out how to get them to be the right size for the Kindle version.

- Some math expressions in the book and chapter tables of contents have weird spacing if they involve subscripts or superscripts. This is an artifact of the Kindle software. This did not happen, for example, when I viewed the book in the Apple Books app.

Share this:

Dancing With Qubits, First Edition: What’s in the book

This morning I awoke to a very nice email from Tom Jacob, the Project Editor for my book at Packt Publishing. He said, in part,

We were able to successfully ship the book to our printers. …

Congratulations on achieving this milestone!

As I’ve mentioned before, my book was prepared using LaTeX and not Microsoft Word. I gave the publishers what was essentially the “camera-ready” PDF file from which to print. Hence the part about being able to “successfully ship” the book. In fact, I sent them the final PDF last night. I thought I was done on Friday, but yesterday I noticed an out-of-place citation in the section on the Bloch sphere and did a quick fix.

Now that the book is in production and there is absolutely nothing else I can do to fiddle with it, I’m going to show you the table of contents. I tried to have fun with some of the chapter and section titles. Once the book is published, I’ll be happy to discuss why I included this content or that.

Dancing with Qubits

How quantum computing works and

how it can change the world

Preface ix

1Â Why Quantum Computing? 1

1.1 The mysterious quantum bit 2

1.2 I’m awake! 4

1.3 Why quantum computing is different 7

1.4 Applications to artificial intelligence 9

1.5 Applications to financial services 15

1.6 What about cryptography? 18

1.7 Summary 21

IÂ Foundations 23

2 They’re Not Old, They’re Classics 25

2.1 What’s inside a computer? 26

2.2 The power of two 32

2.3 True or false? 33

2.4 Logic circuits 36

2.5 Addition, logically 39

2.6 Algorithmically speaking 42

2.7 Growth, exponential and otherwise 42

2.8 How hard can that be? 44

2.9 Summary 55

3Â More Numbers than You Can Imagine 57

3.1 Natural numbers 58

3.2 Whole numbers 60

3.3 Integers 62

3.4 Rational numbers 66

3.5 Real numbers 73

3.6 Structure 88

3.7 Modular arithmetic 94

3.8 Doubling down 96

3.9 Complex numbers, algebraically 97

3.10 Summary 103

4Â Planes and Circles and Spheres, Oh My 107

4.1 Functions 108

4.2 The real plane 111

4.3 Trigonometry 122

4.4 From Cartesian to polar coordinates 129

4.5 The complex “plane†129

4.6 Real three dimensions 133

4.7 Summary 134

5Â Dimensions 137

5.1 R2 and C1 139

5.2 Vector spaces 144

5.3 Linear maps 146

5.4 Matrices 154

5.5 Matrix algebra 166

5.6 Cartesian products 176

5.7 Length and preserving it 177

5.8 Change of basis 189

5.9 Eigenvectors and eigenvalues 192

5.10 Direct sums 198

5.11 Homomorphisms 200

5.12 Summary 204

6 What Do You Mean “Probably� 205

6.1 Being discrete 206

6.2 More formally 208

6.3 Wrong again? 209

6.4 Probability and error detection 210

6.5 Randomness 212

6.6 Expectation 215

6.7 Markov and Chebyshev go to the casino 217

6.8 Summary 221

IIÂ Quantum Computing 223

7Â One Qubit 225

7.1 Introducing quantum bits 226

7.2 Bras and kets 229

7.3 The complex math and physics of a single qubit 234

7.4 A non-linear projection 241

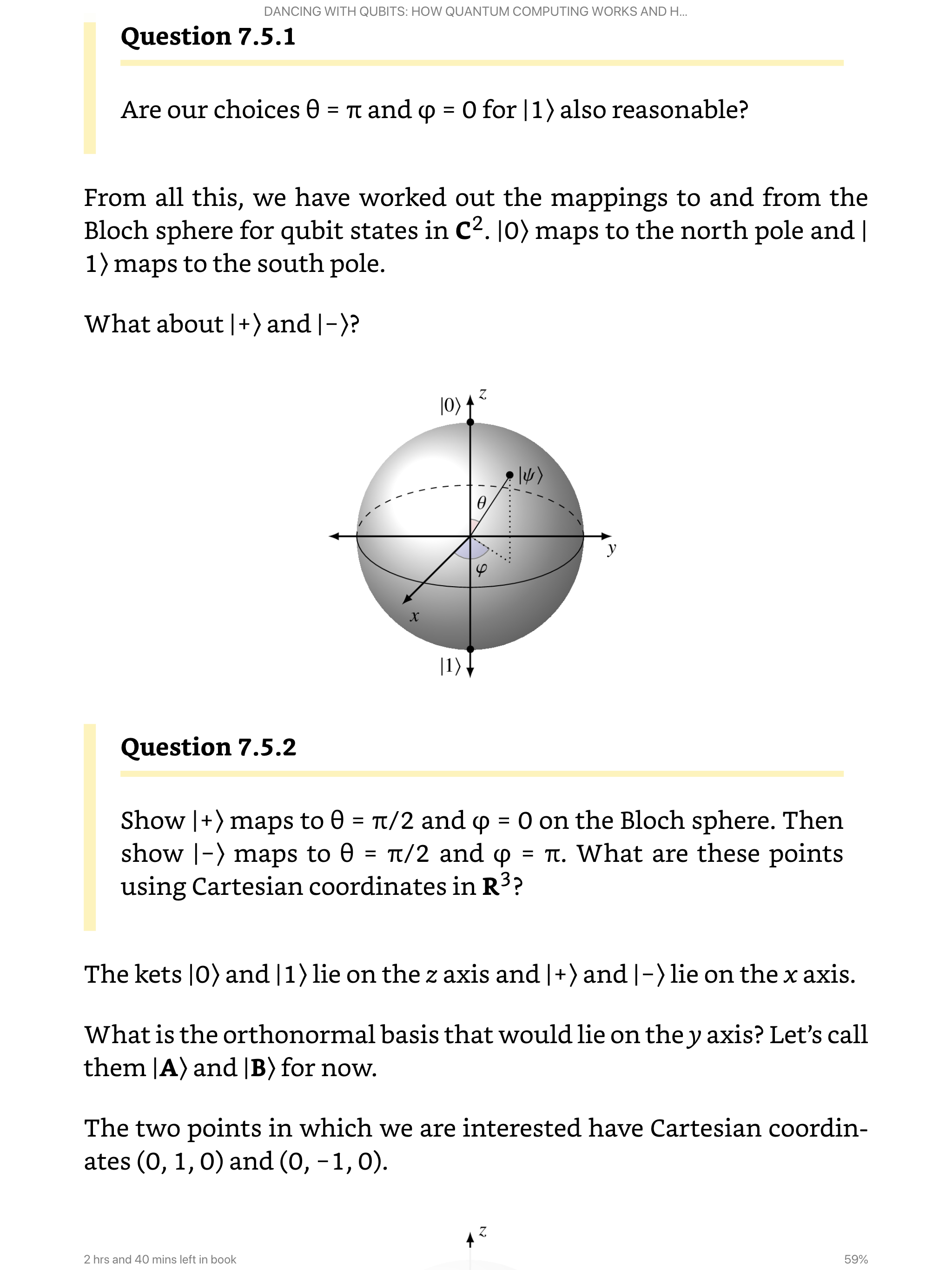

7.5 The Bloch sphere 248

7.6 Professor Hadamard, meet Professor Pauli 253

7.7 Gates and unitary matrices 265

7.8 Summary 266

8Â Two Qubits, Three 269

8.1 Tensor products 270

8.2 Entanglement 275

8.3 Multi-qubit gates 283

8.4 Summary 295

9Â Wiring Up the Circuits 297

9.1 So many gates 298

9.2 From gates to circuits 299

9.3 Building blocks and universality 305

9.4 Arithmetic 315

9.5 Welcome to Delphi 322

9.6 Amplitude amplification 324

9.7 Searching 330

9.8 The Deutsch-Jozsa algorithm 338

9.9 Simon’s algorithm 346

9.10 Summary 354

10Â From Circuits to Algorithms 357

10.1 Quantum Fourier Transform 358

10.2 Factoring 369

10.3 How hard can that be, again 379

10.4 Phase estimation 382

10.5 Order and period finding 388

10.6 Shor’s algorithm 396

10.7 Summary 397

11Â Getting Physical 401

11.1 That’s not logical 402

11.2 What does it take to be a qubit? 403

11.3 Light and photons 406

11.4 Decoherence 415

11.5 Error correction 423

11.6 Quantum Volume 429

11.7 The software stack and access 432

11.8 Simulation 434

11.9 The cat 439

11.10 Summary 441

12Â Questions about the Future 445

12.1 Ecosystem and community 446

12.2 Applications and strategy 447

12.3 Access 448

12.4 Software 449

12.5 Hardware 450

12.6 Education 451

12.7 Resources 452

12.8 Summary 453

Afterword 455

Appendices 458

AÂ Quick Reference 459

A.1 Common kets 459

A.2 Quantum gates and operations 460

BÂ Symbols 463

B.1 Greek letters 463

B.2 Mathematical notation and operations 464

CÂ Notices 467

C.1 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) 467

C.2 Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0) 468

C.3 Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) 468

C.4 Los Alamos National Laboratory 469

C.5 Trademarks 469

DÂ Production Notes 471

Other Books You May Enjoy 473

Index 477

Changes, clarifications, and errata

Previous: Drawing quantum circuits

Next: What about the eBook?

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Share this:

Dancing With Qubits, First Edition: My five rules for making revisions from editorial comments

Today I finished making revisions to the book based on comments from the proofreader. All told, there have been five people providing feedback and comments for how I should modify, fix, and improve the content:

Today I finished making revisions to the book based on comments from the proofreader. All told, there have been five people providing feedback and comments for how I should modify, fix, and improve the content:

- me

- the technical reviewer

- the project editor

- the development editor

- the proof reader

My editing started as soon as I started writing, but it has been an iterative process. The technical reviewer made sure what I said was correct, and occasionally caught typos. The project editor, Tom Jacob, focused on the workflow of the overall process and contributed comments about the physical structure of the book and what publisher content should be included.

The development editor, Dr. Ian Hough, has been my constant online companion for the last few months. It is his responsibility to sign off on the final content. He provided suggestions and ideas, and checked that I made good revisions. Sometimes he corrected the revised text when I made mistakes (hey, it was late!). The proofreader did the nitty-gritty editing for punctuation and clarity. Ian filtered those suggestions and passed them along to me. He then checked, again, that I had done the correct revisions.

Some “suggestions” were really just that. They were optional, but I incorporated almost all of them.

Here are five things I’ve kept in mind or learned through this editing and revision process:

- This is not about my ego, it’s about producing the best content.

- The mathematics and science must be correct. (I knew this!)

- If anyone thinks something is unclear, then I rewrite it.

- I need to use many more commas.

- It’s important to correctly use the right word in standard pairs such as “that/which” and “already/all ready.”

My bonus rule is to eliminate superfluous words.

Previous: The writing process – what format?

Next: Drawing quantum circuits

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Share this:

Dancing With Qubits, First Edition: Let me preface my remarks with …

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

I first got involved with IBM’s quantum computing effort in early 2016. By 2018, I was again thinking of writing a book and this subject was an obvious candidate. How would I start? What would I say? What was my perspective on the topic given that there were already some excellent books?

To write a book, you have to start writing. This is obvious, but no less true and important. In the summer of 2018, I started writing what I thought would be the introduction to the book. My perspective was, and is, very much from the mathematical and computer science directions. To be clear, I am not a physicist. If I could produce a coherent introduction to what I thought the book would cover, I might convince myself that it would be worth the hundreds of hours it would take to complete the project.

When I recently announced that the book was available for pre-order, my industry colleague Jason Bloomberg asked:

“So where does it fall on the spectrum between ‘totally accurate yet completely impenetrable’ and ‘approachable by normal humans but a complete whitewash’?”

I responded:

“I bring you along … to give you the underlying science of quantum computing so you can then read the “totally accurate but formally impenetrable” texts.”

I decided that I would cover the basic math necessary to understand quantum computing, and then get into quantum bits (qubits), gates, circuits, and algorithms. Although readers with the necessary background (or perhaps a good memory of that background) can skip the mathematical fundamentals, I decided to take people through the algebra and geometry of complex numbers, linear algebra, and probability necessary to understand what qubits are and what you can do with them.

That early draft of the book’s introduction described roughly 15 chapters divided into three parts. The final book has 12 chapters and 2 parts. That introduction eventually became the Preface. Part III eventually became Chapter 1.

It’s much tighter than what I imagined it would be, but there is still material I could have covered. There’s a natural tendency to want to add more and more, but I kept asking myself “What is this book about? How deeply do I want to go? Am I getting off track? Will I ever finish?”.

As 2018 went on, I kept tweaking the introduction and I started talking to publishers. In November, I started writing what was then the first chapter. Although I started in Microsoft Word, which is overwhelmingly the format of choice for many publishers, I quickly switched to LaTeX. This produced a far more beautiful book, but also placed constraints on how I could publish the book.

With this as teaser, in future entries I’ll talk more about the writing process, choices I made, LaTeX packages I used and macros I wrote, deciding how to publish the book, and working with editors. Once the book is available, I’ll talk about the specific content and why I included what I did.

Next: Last minute tweaks to my quantum computing book cover

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Share this:

Math and Analytics at IBM Research: 50+ Years

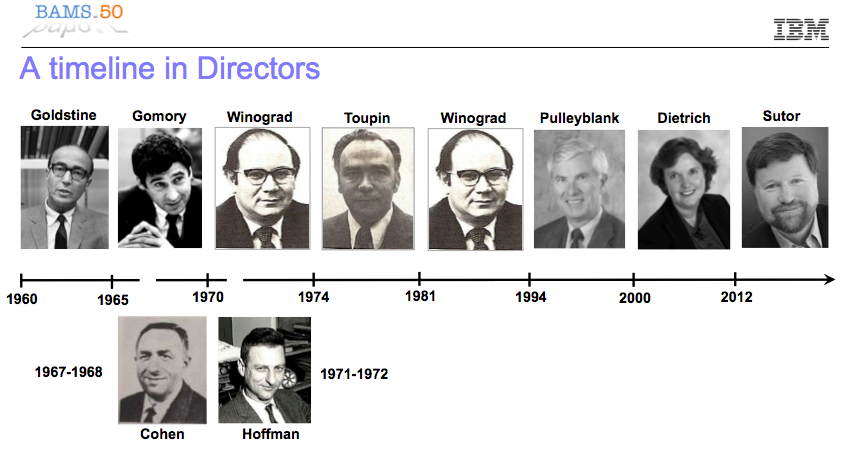

Soon after I arrived back in IBM Research last July after 13 years away in the Software Group and Corporate, I was shown a 2003 edition of the IBM Journal of Research and Development that was dedicated to the Mathematical Sciences group at 40. From that, I and others assumed that this year, 2013, was the 50th anniversary of the department.

I set about lining up volunteers to organize the anniversary events for the year and sent an email to our 300 worldwide members of what is now called the Business Analytics and Mathematical Sciences strategy area. Not long afterwards, I received a note from Alan Hoffman, a former director of the department, saying that he was pretty sure that the department had been around since 1958 or 59. So our 50th Anniversary became the 50+ Anniversary. Evidently mathematicians know the theory of arithmetic but don’t always practice it correctly

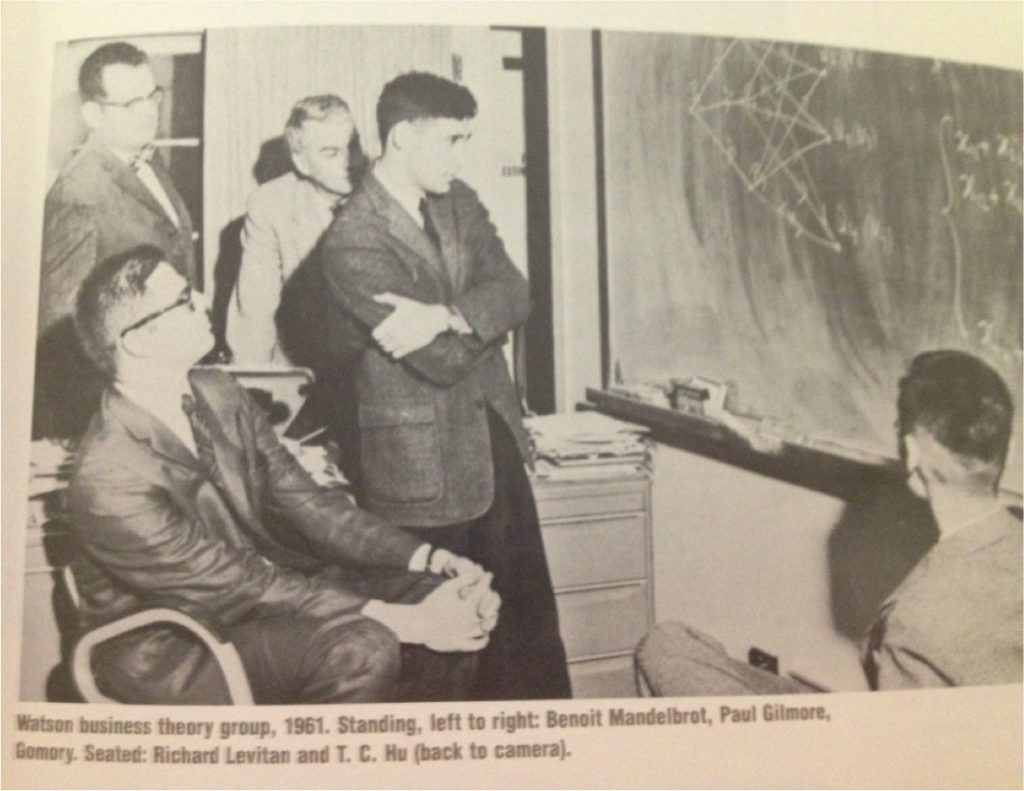

The first director of the department was Herman Goldstine who joined after working on the ENIAC computer and a stint at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Goldstine is pictured in the first photo on the right at a reception at the T.J. Watson Research Center in the early 1960s. Goldstine died in 2004, but all other directors of the department are still alive.

We decided that the first event of the year celebrating the (more than) half century of the department would be a reunion of the directors for a morning of panel discussions. This took place this last Wednesday, May 1, 2013.

I started the day by giving a glimpse of what the department looks like today: the above-mentioned 300 Ph.D.s, software engineers, postdocs, and other staff distributed over the areas of optimization, analytics, visual analytics, and social business in 10 of IBM’s 12 global labs.

I then introduced our panel pictured in the photo above. From left to right we have me, Brenda Dietrich,

My goal for the discussion was to go back and look at some of the history and culture of the math department over the last five decades. I was hoping we would hear anecdotes and stories of what life was like, the challenges they faced, and the major successes and disappointments.

Other than a few questions I had prepared, I wasn’t sure where our conversation would go. The many researchers who joined us in the auditorium at the T. J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, NY, or via the video feed going out to the other worldwide labs would have a chance to ask questions near the end of the morning.

I’m not going to go over every question and answer but rather give you the gist of what we spoke about.

- Ralph Gomory reminded us that the department was started in a much different time, during the Cold War. The problems they were trying to solve using the hardware and the software of the day were often related highly confidential. However, every era of the department has had its own focus, burning problems to be solved, and operational environment.

- Hirsh Cohen got his inspiration for the mathematics he did by solving practical problems such as those related to the large mainframe-connected printers. Many people feel that mathematics shouldn’t stray too far from the concrete, but it is not that simple. This isn’t just applied mathematics, it is a way of looking for inspiration that may express itself in more theoretical ways. The panelists mentioned more than once that the original posers of business or engineering problems might not recognize the mathematics that was developed in response. (I think there is nothing wrong with theoretical mathematics with no direct connection to the physical world, but there are some areas of mathematical pursuit that I think are just silly and of marginal pure or applied interest.)

- In response to my question about balancing business needs with the desire to advance basic science, Shmuel Winograd told me I had asked the wrong question: it was about the integration of business with basic science, not a partitioning of time or resources between them. This very much sets the tone of how you manage such a science organization in a commercial company. The successful integration of these concerns may also be why IBM Research is pretty much the sole survivor of the industrial research labs from the 1950s and 1960s.

- There was general consensus that it is difficult to get a researcher to do science in an area that he or she fundamentally does not want to work. This was redirected to the audience members who were reminded to understand what they loved to do and then find a way to do it. (This sounded like a bit of a management challenge to me, and I suspect I’ll hear about it again.)

- Time gives a great perspective on the quality and significance of scientific work that is just not obvious while you are the middle of it. This is one of the reasons why retrospectives such as this can be so satisfying.

After the first panel and coffee break, we came back and I started the session looking at the future of the department instead of the history. We have an internal department social network community in IBM Connections and I started by summarizing some of the suggestions people came up with about what we’ll be doing in the department in five, ten, and twenty years.

Sustainability, robotic applications of cognitive computing, and mathematical algorithms for quantum computing were all suggested. Note that his was all fun speculation, not strategy development!

Eleni Pratsini, Director of Optimization Research, and Chid Apte, Director of Analytics Research, then each discussed technical topics that could be future areas for scientific research as well as having significant business use.

After the final Q&A session, we got everyone on stage for a group photo.

One thing that struck me when we were doing the research through the archives was how much more of a record we have of the first decade of the department than we do of the 40+ years afterwards. In those early days, each department did a typed report of its activities which was then sent to management and archived.

With the increasing use of email and, much later, digital photos, we just don’t have easy if any access to what happened month by month. As part of this 50+ Anniversary, I’m going to organize an effort to do a better job of finding and cataloging the documents, photos, and video of the department.

This should make it easier for future celebrations of the department’s history. I suspect I’m not going to make it to the 100th anniversary, but I just might get to the 75th. For the record for those who come after me, that will be in 2034.