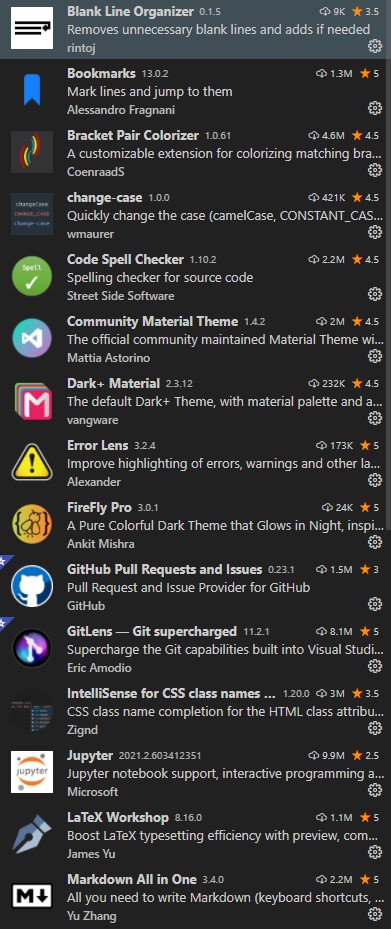

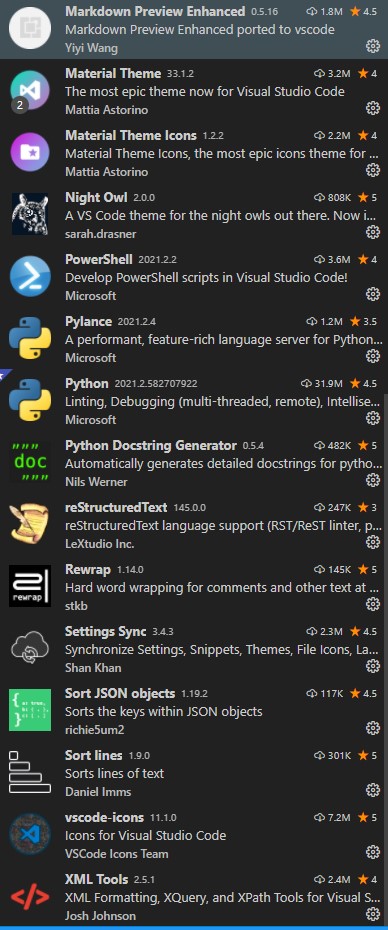

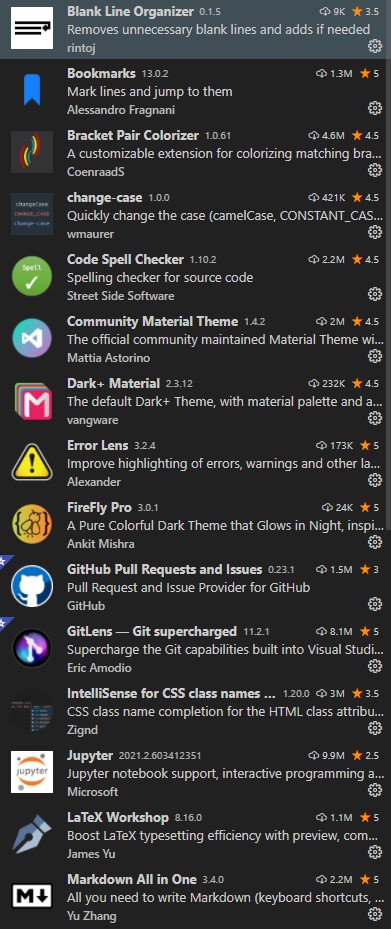

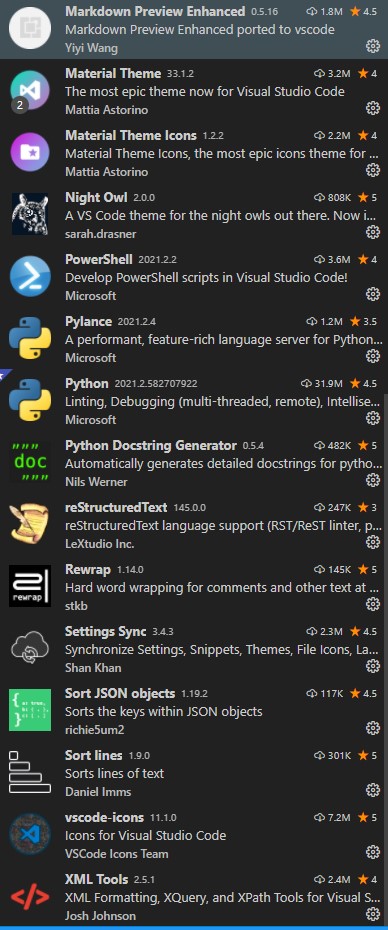

I use about 30 extensions for Python, HTML, CSS, Markdown, and LaTeX, plus a few others for general editing.

|

|

Tech Executive | Author | Advisor | Keynote Speaker | Analyst | Professor

I use about 30 extensions for Python, HTML, CSS, Markdown, and LaTeX, plus a few others for general editing.

|

|

I’m pleased to announce that the Amazon Kindle version of my quantum computing book Dancing with Qubits is now available!

I’m pleased to announce that the Amazon Kindle version of my quantum computing book Dancing with Qubits is now available!

This book provides a comfortable and conversational introduction to quantum computing. I take you through the mathematics you need at a pace that allows you to understand not just “what” but also “why.” When we get to quantum computing, concepts like superposition and entanglement are shown to be natural ideas building on what we’ve already seen, and then illustrated via gates, circuits, and algorithms.

Throughout the book, I highlight important results, provide questions to answer, and give links to references where you can learn more. This allows the book to be used for self-study or as a textbook.

Important ideas like Quantum Volume are explained to give you a head start for reading more advanced texts and research papers. I provide many references to related content in math, physics, quantum computing, AI, and financial services. Dancing with Qubits concludes with questions for you to think about and ask experts so that you can gauge progress in the field over the next few years.

The print version of Dancing with Qubits still has the full, rich mathematical formatting, albeit in black and white. In essence, whether you choose the print or Kindle version, the content is consistent and the formatting is the best I know how to produce for each medium.

Here are a few comments about the production of the Kindle version, in case you are interested.

Yesterday was very exciting because I received my first printed copy of the book. There’s just something about holding a physical, printed book that you’ve labored over for many months. Others are starting to get their copies too, and I hope that within a couple of weeks everyone who pre-ordered the print version will have copies in hand.

Yesterday was very exciting because I received my first printed copy of the book. There’s just something about holding a physical, printed book that you’ve labored over for many months. Others are starting to get their copies too, and I hope that within a couple of weeks everyone who pre-ordered the print version will have copies in hand.

What if you ordered the eBook? Wasn’t that an option on Amazon? Why isn’t it listed there now? Why was your Kindle eBook order canceled?

The original plan was to provide the eBook in a PDF-like, print replica format that was in color and had active links within and beyond the book. You can still purchase this eBook at the Packt Publishing website.

As for Amazon, let’s just say that they ultimately wanted a reflowable version of the book rather than a fixed format version. As I’ve mentioned before, this presents many challenges to producing beautiful math. The reflowable format allows you to change the font and font size you use on your Kindle or in the Kindle app. It makes it easier to read on small devices. I understand the value.

Hence, I’m now working to create a reflowable version with one guiding principle: as much as possible, I must have a single source for the book that will produce future versions of the printed, fixed-format PDF, and reflowable formats

Here’s the strategy:

There is much work to do but things are looking promising. I can’t now give you any estimated time of arrival for the Kindle reflowable version or any guarantee that it will arrive eventually, but it’s my strong intention to make it happen. There are unknown unknowns yet to be discovered.

In the meanwhile, as I mentioned above, you can get a PDF-like digital version of the book from Packt.

A final point: despite several people staring at the text, a few errors crept in. These are mostly typos or omitted words. I’m keeping track of these on the corrections and clarifications page for the book. I incorporate these fixes into the text as they are discovered and I hope that future versions of the book, printed and digital, include them.

Previous: What’s in the book

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

This morning I awoke to a very nice email from Tom Jacob, the Project Editor for my book at Packt Publishing. He said, in part,

We were able to successfully ship the book to our printers. …

Congratulations on achieving this milestone!

As I’ve mentioned before, my book was prepared using LaTeX and not Microsoft Word. I gave the publishers what was essentially the “camera-ready” PDF file from which to print. Hence the part about being able to “successfully ship” the book. In fact, I sent them the final PDF last night. I thought I was done on Friday, but yesterday I noticed an out-of-place citation in the section on the Bloch sphere and did a quick fix.

Now that the book is in production and there is absolutely nothing else I can do to fiddle with it, I’m going to show you the table of contents. I tried to have fun with some of the chapter and section titles. Once the book is published, I’ll be happy to discuss why I included this content or that.

Dancing with Qubits

How quantum computing works and

how it can change the world

Preface ix

1Â Why Quantum Computing? 1

1.1 The mysterious quantum bit 2

1.2 I’m awake! 4

1.3 Why quantum computing is different 7

1.4 Applications to artificial intelligence 9

1.5 Applications to financial services 15

1.6 What about cryptography? 18

1.7 Summary 21

IÂ Foundations 23

2 They’re Not Old, They’re Classics 25

2.1 What’s inside a computer? 26

2.2 The power of two 32

2.3 True or false? 33

2.4 Logic circuits 36

2.5 Addition, logically 39

2.6 Algorithmically speaking 42

2.7 Growth, exponential and otherwise 42

2.8 How hard can that be? 44

2.9 Summary 55

3Â More Numbers than You Can Imagine 57

3.1 Natural numbers 58

3.2 Whole numbers 60

3.3 Integers 62

3.4 Rational numbers 66

3.5 Real numbers 73

3.6 Structure 88

3.7 Modular arithmetic 94

3.8 Doubling down 96

3.9 Complex numbers, algebraically 97

3.10 Summary 103

4Â Planes and Circles and Spheres, Oh My 107

4.1 Functions 108

4.2 The real plane 111

4.3 Trigonometry 122

4.4 From Cartesian to polar coordinates 129

4.5 The complex “plane†129

4.6 Real three dimensions 133

4.7 Summary 134

5Â Dimensions 137

5.1 R2 and C1 139

5.2 Vector spaces 144

5.3 Linear maps 146

5.4 Matrices 154

5.5 Matrix algebra 166

5.6 Cartesian products 176

5.7 Length and preserving it 177

5.8 Change of basis 189

5.9 Eigenvectors and eigenvalues 192

5.10 Direct sums 198

5.11 Homomorphisms 200

5.12 Summary 204

6 What Do You Mean “Probably� 205

6.1 Being discrete 206

6.2 More formally 208

6.3 Wrong again? 209

6.4 Probability and error detection 210

6.5 Randomness 212

6.6 Expectation 215

6.7 Markov and Chebyshev go to the casino 217

6.8 Summary 221

IIÂ Quantum Computing 223

7Â One Qubit 225

7.1 Introducing quantum bits 226

7.2 Bras and kets 229

7.3 The complex math and physics of a single qubit 234

7.4 A non-linear projection 241

7.5 The Bloch sphere 248

7.6 Professor Hadamard, meet Professor Pauli 253

7.7 Gates and unitary matrices 265

7.8 Summary 266

8Â Two Qubits, Three 269

8.1 Tensor products 270

8.2 Entanglement 275

8.3 Multi-qubit gates 283

8.4 Summary 295

9Â Wiring Up the Circuits 297

9.1 So many gates 298

9.2 From gates to circuits 299

9.3 Building blocks and universality 305

9.4 Arithmetic 315

9.5 Welcome to Delphi 322

9.6 Amplitude amplification 324

9.7 Searching 330

9.8 The Deutsch-Jozsa algorithm 338

9.9 Simon’s algorithm 346

9.10 Summary 354

10Â From Circuits to Algorithms 357

10.1 Quantum Fourier Transform 358

10.2 Factoring 369

10.3 How hard can that be, again 379

10.4 Phase estimation 382

10.5 Order and period finding 388

10.6 Shor’s algorithm 396

10.7 Summary 397

11Â Getting Physical 401

11.1 That’s not logical 402

11.2 What does it take to be a qubit? 403

11.3 Light and photons 406

11.4 Decoherence 415

11.5 Error correction 423

11.6 Quantum Volume 429

11.7 The software stack and access 432

11.8 Simulation 434

11.9 The cat 439

11.10 Summary 441

12Â Questions about the Future 445

12.1 Ecosystem and community 446

12.2 Applications and strategy 447

12.3 Access 448

12.4 Software 449

12.5 Hardware 450

12.6 Education 451

12.7 Resources 452

12.8 Summary 453

Afterword 455

Appendices 458

AÂ Quick Reference 459

A.1 Common kets 459

A.2 Quantum gates and operations 460

BÂ Symbols 463

B.1 Greek letters 463

B.2 Mathematical notation and operations 464

CÂ Notices 467

C.1 Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) 467

C.2 Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0) 468

C.3 Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) 468

C.4 Los Alamos National Laboratory 469

C.5 Trademarks 469

DÂ Production Notes 471

Other Books You May Enjoy 473

Index 477

Changes, clarifications, and errata

Previous: Drawing quantum circuits

Next: What about the eBook?

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

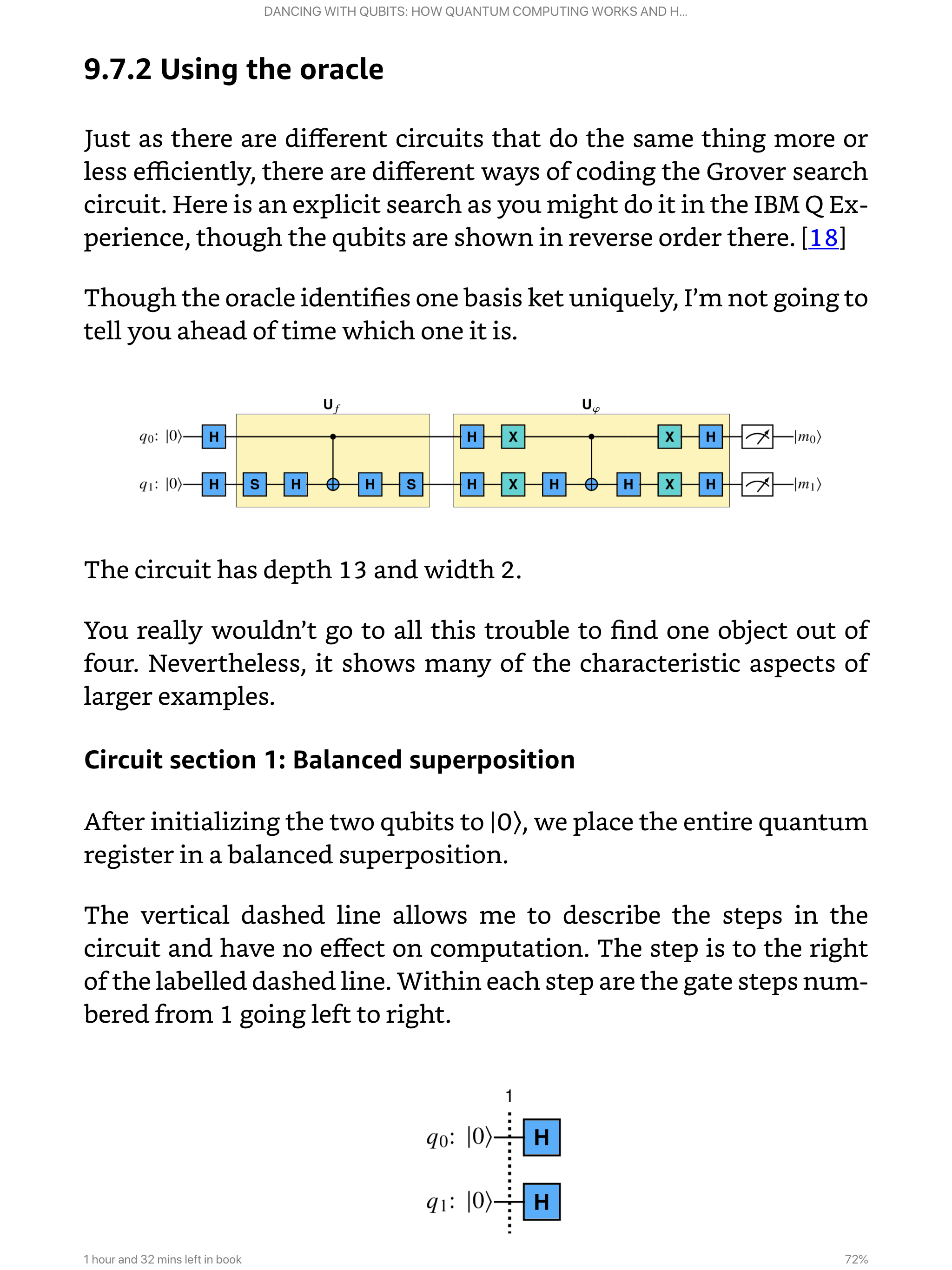

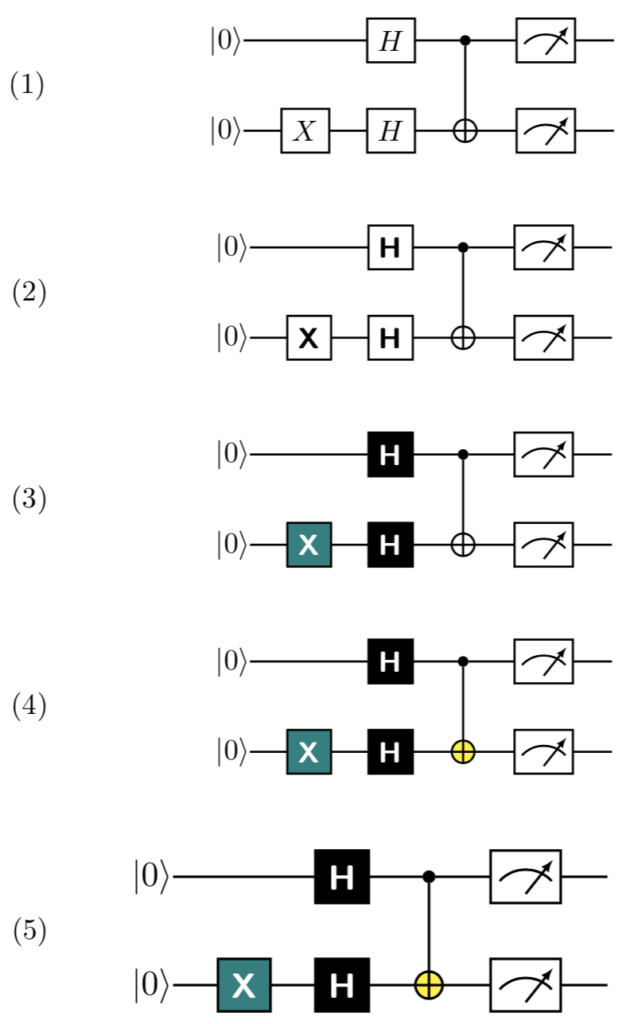

An early decision I had to make was how to draw quantum circuit diagrams in the book. Here’s an example of one:

This includes three Hadamard H gates, two S gates, a T gate, and a swap gate. Would I need to write my own drawing routines?

I really didn’t want to do that because of my time constraints but I also hoped that I could find something better. It didn’t take me long to do so: Alastair Kay’s excellent quantikx package on the CTAN Comprehensive TeX Archive Network. The documentation there is very good, but in this blog entry I’m going to show you how to evolve a simple circuit to have stylistic customizations that you might want to modify and use.

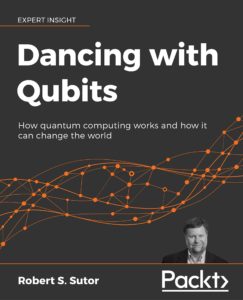

Below are five displayed versions of the same circuit. They are numbered on the left side.

The first is the default formatting from quantikz. It is perfectly fine and you can see similarly formatted circuits in research articles about quantum computing.

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \gate{H} & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \gate{X} & \gate{H} & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

The markup \ket{0} produces the |0> at the beginning of each wire, which is a horizontal line. \qw creates a segment of a quantum wire. \gate is the basic command for drawing a labeled gate with a rectangle. \meter is the quantum measurement operator. \ctrl{1} and \targ{} are the two parts of a CNOT two-qubit gate. \ctrl{1} is on the wire for the control qubit and extends a line down one wire. There the line meets the \targ{} (target) qubit and is drawn as a circle around a “+” sign.

In the second example, I’ve changed the font in the H and X gates.

\newcommand*{\gateStyle}[1]{{\textsf{\bfseries #1}}}

\newcommand*{\hGate}{\gateStyle{H}}

\newcommand*{\xGate}{\gateStyle{X}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \gate{\hGate} & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \gate{\xGate} & \gate{\hGate} & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

I added three LaTeX macros to encapsulate the new function and make it easier to reuse.

\gatestyle puts its text in a bold sans serif font.\hGate draws the Hadamard H using \gatestyle.\xGate draws the X using \gatestyle.While it is now easier to use \hGate and \xGate for text, it’s still wordy to use them as gates in a circuit. The third example defines two more macros, \circuitH and \circuitX, and shows how to set the background and font colors. For a printed book, you might want to have gates with backgrounds in different shades of gray. Alternatively, you could use the same background color for all the Clifford gates.

\newcommand*{\circuitH}{\gate[style={fill=black},label style=white]{\textnormal{\hGate{}}}}

\newcommand*{\circuitX}{\gate[style={fill=teal},label style=white]{\textnormal{\xGate}}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

Now let’s set the color for the circle in \targ.

\newcommand*{\circuitTarget}[1]{\targ[style={fill=yellow}]{#1}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \circuitTarget{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

I think you get the idea. You can also set the background color for \meter, which I leave to you as an exercise. Note that in the April, 2019, version of quantikx, you could not change the color of the line inside the \meter graphic. You need to copy and redefine the macro (or create a new macro) to do that.

Finally, let me explain what that [scale=1.0] is doing after the \node. This allows you to scale the entire drawing and make it larger or smaller. However, it does not change the text size. The fifth example shows the fourth example drawn 20

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node[scale=1.2] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \circuitTarget{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

Here is the complete LaTeX file I used to generate the examples:

\usetikzlibrary{quantikz}

\mainmatter

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node at (-5,0) {(1)};

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \gate{H} & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \gate{X} & \gate{H} & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

\newcommand*{\gateStyle}[1]{{\textsf{\bfseries #1}}}

\newcommand*{\hGate}{\gateStyle{H}}

\newcommand*{\xGate}{\gateStyle{X}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node at (-5,0) {(2)};

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \gate{\hGate} & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \gate{\xGate} & \gate{\hGate} & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

\newcommand*{\circuitH}{\gate[style={fill=black},label style=white]{\textnormal{\hGate{}}}}

\newcommand*{\circuitX}{\gate[style={fill=teal},label style=white]{\textnormal{\xGate}}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node at (-5,0) {(3)};

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \targ{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

\newcommand*{\circuitTarget}[1]{\targ[style={fill=yellow}]{#1}}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node at (-5,0) {(4)};

\node[scale=1.0] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \circuitTarget{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

\begin{center}

\begin{tikzpicture}

\node at (-4.4,0) {(5)};

\node[scale=1.2] {

\begin{quantikz}

\ket{0} & \qw & \circuitH & \ctrl{1} & \meter{} & \qw \\

\ket{0} & \circuitX & \circuitH & \circuitTarget{} & \meter{} & \qw

\end{quantikz}

};

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{center}

Previous: My five rules for making revisions from editorial comments

Next: What’s in the book

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Before I discuss what and I how I wrote, let me talk about the markup of the book. By “markup” I mean the underlying format of the content that determines its structure such as the title page, table of contents, parts, chapters, sections, paragraphs, bibliography, and the index, along with font styles and sizes.

Before I discuss what and I how I wrote, let me talk about the markup of the book. By “markup” I mean the underlying format of the content that determines its structure such as the title page, table of contents, parts, chapters, sections, paragraphs, bibliography, and the index, along with font styles and sizes.

In my experience, most publishers, both traditional and online, prefer you to use Microsoft Word to create the book, and it has its own underlying markup language that you typically never see. In a more-or-less what-you-see-is-what-you-get way, you can write and style the book.The publishing workflow is often based on this choice.

My requirements for the book creation process included:

Regarding the size of the book, in early 2019 I thought the book would come in around 300 pages and I would have a complete draft on September 1. I ended up writing a book with slightly more than 500 pages with the first full draft delivered on October 9. I had full drafts of various chapters before then, but that was the first time there were no sections with TODO markers.

Word has come a long way on many of these requirements, especially the math, though it can be very laborious to create a book with hundreds or thousands of formulas. Here’s the real problem though: eBooks with math in them often look terrible if you put them in a reflowable format. That is, if you let, say, your Amazon Kindle change the fonts and the line widths, the math just doesn’t look right.

Word has come a long way on many of these requirements, especially the math, though it can be very laborious to create a book with hundreds or thousands of formulas. Here’s the real problem though: eBooks with math in them often look terrible if you put them in a reflowable format. That is, if you let, say, your Amazon Kindle change the fonts and the line widths, the math just doesn’t look right.

People argue about this forever, but there is an excellent chance that you will end up with fuzzy, misaligned expressions that are the wrong size compared to the surrounding text. So, I early on made the decision that the eBook would not be reflowable. Since that was the case, there was no reason for me to stick with Word. I decided to markup the book in LaTeX. Luckily, Andrew Waldron at Packt Publishing agreed. [Though see this later development regarding the eBook.]

With LaTeX, you have complete and arbitrary control over all parts of the formatting. There are thousands of packages that make your life easier by providing significant functionality that you would not want to write yourself.

LaTeX has

If you get into macro programming, things can get complicated. I’ve been doing it for 30 years, so it doesn’t faze me. Here are two good books on LaTeX to get you started:

Previous: Last minute tweaks to my quantum computing book cover

Next: My five rules for making revisions from editorial comments

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

I first got involved with IBM’s quantum computing effort in early 2016. By 2018, I was again thinking of writing a book and this subject was an obvious candidate. How would I start? What would I say? What was my perspective on the topic given that there were already some excellent books?

To write a book, you have to start writing. This is obvious, but no less true and important. In the summer of 2018, I started writing what I thought would be the introduction to the book. My perspective was, and is, very much from the mathematical and computer science directions. To be clear, I am not a physicist. If I could produce a coherent introduction to what I thought the book would cover, I might convince myself that it would be worth the hundreds of hours it would take to complete the project.

When I recently announced that the book was available for pre-order, my industry colleague Jason Bloomberg asked:

“So where does it fall on the spectrum between ‘totally accurate yet completely impenetrable’ and ‘approachable by normal humans but a complete whitewash’?”

I responded:

“I bring you along … to give you the underlying science of quantum computing so you can then read the “totally accurate but formally impenetrable” texts.”

I decided that I would cover the basic math necessary to understand quantum computing, and then get into quantum bits (qubits), gates, circuits, and algorithms. Although readers with the necessary background (or perhaps a good memory of that background) can skip the mathematical fundamentals, I decided to take people through the algebra and geometry of complex numbers, linear algebra, and probability necessary to understand what qubits are and what you can do with them.

That early draft of the book’s introduction described roughly 15 chapters divided into three parts. The final book has 12 chapters and 2 parts. That introduction eventually became the Preface. Part III eventually became Chapter 1.

It’s much tighter than what I imagined it would be, but there is still material I could have covered. There’s a natural tendency to want to add more and more, but I kept asking myself “What is this book about? How deeply do I want to go? Am I getting off track? Will I ever finish?”.

As 2018 went on, I kept tweaking the introduction and I started talking to publishers. In November, I started writing what was then the first chapter. Although I started in Microsoft Word, which is overwhelmingly the format of choice for many publishers, I quickly switched to LaTeX. This produced a far more beautiful book, but also placed constraints on how I could publish the book.

With this as teaser, in future entries I’ll talk more about the writing process, choices I made, LaTeX packages I used and macros I wrote, deciding how to publish the book, and working with editors. Once the book is available, I’ll talk about the specific content and why I included what I did.

Next: Last minute tweaks to my quantum computing book cover

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

I’m in the final stages of writing a book about quantum computing using LaTeX and I also do a lot of Python programming when I get a chance. A couple of years ago, I decided to try using the Visual Studio Code editor and I just love it. I’ve used dozens of programming editors in my life (vi, not emacs, thank you very much), and VSCode has the best functionality of all of them.

One of its best features is its extension architecture. Though I experiment with various extensions occasionally, I keep a core set. If I am going to so something special such as editing Markdown text, I will use an extra extension or two until I am done with the task and then uninstall them.

These are the extensions I use now for LaTeX editing and Python coding. They are all available in the editor through the Marketplace.

I’m writing something that requires me to draw many plots in the Cartesian plane R2 and so I wrote this macro to simplify the process. The arguments are

It behaves nicely if any of the coordinates are 0 but does no checking for the values or placement of the corners.

I have a separate macro \tikzGridColor that defines the grid color. At the moment it is set to a shade of blue so the graph looks like it is done on graph paper.

Scroll right to see all the code.

[sourcecode language=”tex”]

\usetikzlibrary{angles,quotes,arrows,positioning}

\usetikzlibrary{arrows.meta,calc,patterns}

\usetikzlibrary{decorations.pathreplacing,backgrounds}

\def\tikzGridColor{blue!75!white}

\newcommand{\graphGridTwoD}[7][0.5]{

\draw[step=#1,\tikzGridColor,very thin] (#2-0.9,#3-0.9) grid (#4+0.9,#5+0.9);

\draw[thick,<->] (#2-0.75,0) — (#4+0.75,0) node[below] {\small #6};

\draw[thick,<->] (0,#3-0.75) — (0,#5+0.75) node[left] {\small #7};

\ifthenelse{#2<0}

{\foreach \x in {#2,…,-1}

\draw[thick] (\x,.1) — (\x,-.1) node[below] {\tiny$\x$};

}{}

\ifthenelse{#4>0}

{\foreach \x in {1,…,#4}

\draw[thick] (\x,.1) — (\x,-.1) node[below] {\tiny$\x$};

}{}

\ifthenelse{#3<0}

{\foreach \y in {#3,…,-1}

\draw[thick] (.1,\y) — (-.1,\y) node[left] {\tiny$\y$};

}{}

\ifthenelse{#5>0}

{\foreach \y in {1,…,#5}

\draw[thick] (.1,\y) — (-.1,\y) node[left] {\tiny$\y$};

}{}

\node[below left] at (0,0) {\tiny$0$};

}

[/sourcecode]