I have a running YouTube playlist about quantum computing where I capture videos mostly about quantum computing in general, IBM Quantum, the Qiskit open source quantum computing development environment, and my book Dancing with Qubits.

IBM

Podcast: Meet the meQuanics with Simon Devitt and me

My podcast with Simon Devitt discussing quantum computing, IBM Quantum, and my new book Dancing with Qubits is now available on Spotify.

Dancing With Qubits, First Edition: Let me preface my remarks with …

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

Way back in 1992, Springer-Verlag published my first book Axiom: The Scientific Computation System, co-authored with the late Richard D. Jenks. Since then I’ve thought of writing other books, but work and life in general caused enough inertia that I never got around to it.

I first got involved with IBM’s quantum computing effort in early 2016. By 2018, I was again thinking of writing a book and this subject was an obvious candidate. How would I start? What would I say? What was my perspective on the topic given that there were already some excellent books?

To write a book, you have to start writing. This is obvious, but no less true and important. In the summer of 2018, I started writing what I thought would be the introduction to the book. My perspective was, and is, very much from the mathematical and computer science directions. To be clear, I am not a physicist. If I could produce a coherent introduction to what I thought the book would cover, I might convince myself that it would be worth the hundreds of hours it would take to complete the project.

When I recently announced that the book was available for pre-order, my industry colleague Jason Bloomberg asked:

“So where does it fall on the spectrum between ‘totally accurate yet completely impenetrable’ and ‘approachable by normal humans but a complete whitewash’?”

I responded:

“I bring you along … to give you the underlying science of quantum computing so you can then read the “totally accurate but formally impenetrable” texts.”

I decided that I would cover the basic math necessary to understand quantum computing, and then get into quantum bits (qubits), gates, circuits, and algorithms. Although readers with the necessary background (or perhaps a good memory of that background) can skip the mathematical fundamentals, I decided to take people through the algebra and geometry of complex numbers, linear algebra, and probability necessary to understand what qubits are and what you can do with them.

That early draft of the book’s introduction described roughly 15 chapters divided into three parts. The final book has 12 chapters and 2 parts. That introduction eventually became the Preface. Part III eventually became Chapter 1.

It’s much tighter than what I imagined it would be, but there is still material I could have covered. There’s a natural tendency to want to add more and more, but I kept asking myself “What is this book about? How deeply do I want to go? Am I getting off track? Will I ever finish?”.

As 2018 went on, I kept tweaking the introduction and I started talking to publishers. In November, I started writing what was then the first chapter. Although I started in Microsoft Word, which is overwhelmingly the format of choice for many publishers, I quickly switched to LaTeX. This produced a far more beautiful book, but also placed constraints on how I could publish the book.

With this as teaser, in future entries I’ll talk more about the writing process, choices I made, LaTeX packages I used and macros I wrote, deciding how to publish the book, and working with editors. Once the book is available, I’ll talk about the specific content and why I included what I did.

Next: Last minute tweaks to my quantum computing book cover

| In December, 2019, Packt Publishing published my book Dancing with Qubits: How quantum computing works and how it can change the world. Through a series of blog entries, I talk about the writing and publishing process, and then about the content. |

Bloomberg Radio interview

I had a great time talking to Lisa Abramowicz at Bloomberg Radio in New York City this morning about quantum computing and IBM Q. You can listen to a recording of it online.

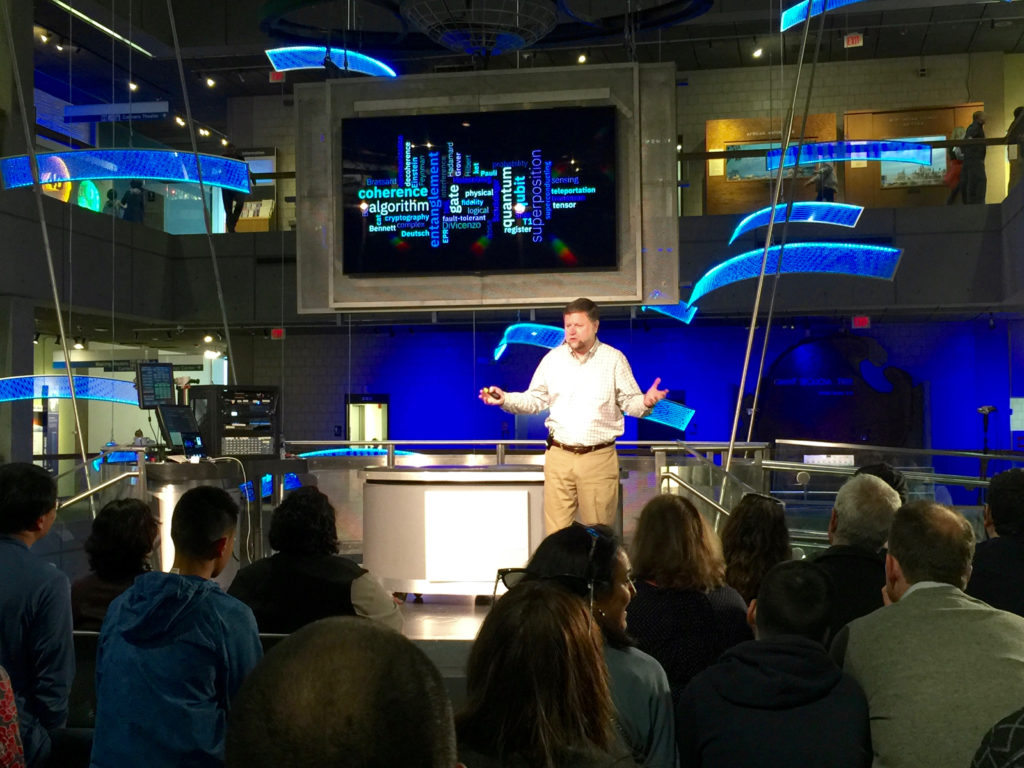

Recap: NanoDays with a Quantum Leap at the Museum of Science, Boston

It was a beautiful spring day in Boston last Saturday, April 6, when my IBM Q colleague Melissa Turesky and I headed to the Museum of Science on the Charles River. It was a special event, “NanoDays with a Quantum Leap,” and I spoke about the IBM Q quantum computing program and how people could start coding it today.

I was most happy to see how many young people were at the museum and participating in the NanoDays events. A lot of what we are doing now with quantum computing is education and I hope that exhibits like this will encourage girls and boys to learn more about the area. I’d love to have someone tell me in 10 years that the museum exhibit inspired them to pursue a quantum-related STEM career.

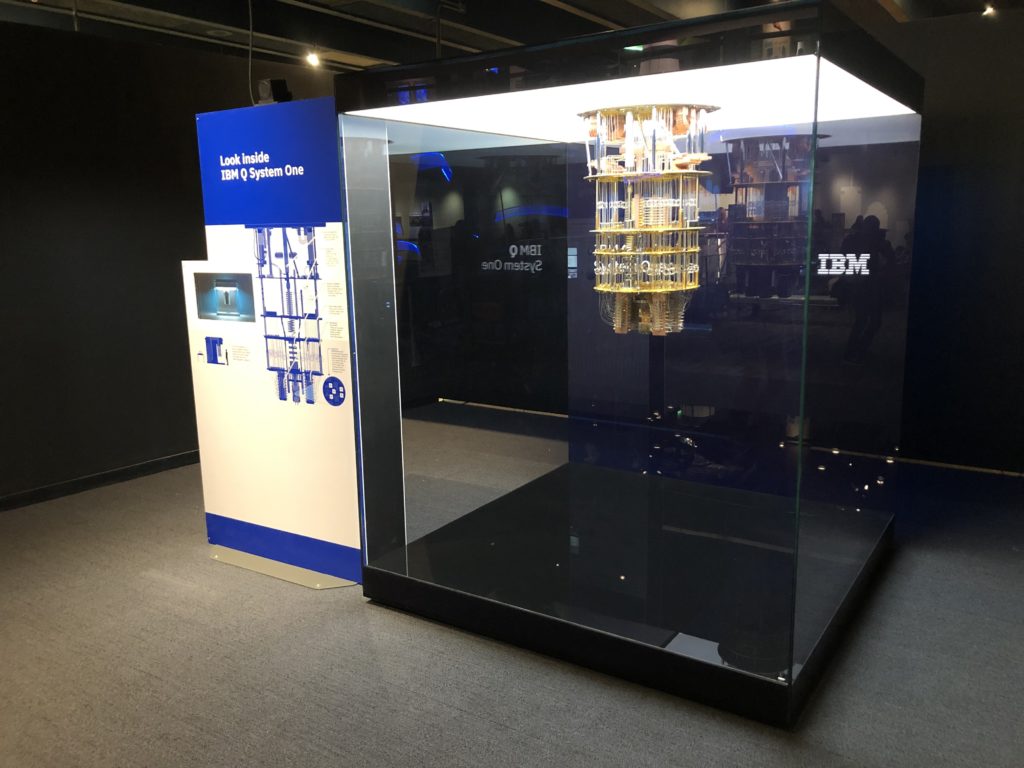

Since 2016, over 100,000 people have used the IBM Q Experience and they have run over 9.5M executions. A 50 qubit model of the IBM Q System One will be in residence as part of the quantum exhibit until the end of May.

My #BCTECHSummit 2019 talk

I spoke this morning about quantum computing at #BCTECHSummit in Vancouver, British Columbia. Here are some of the points I emphasized:

- The mainstream efforts including IBM Q are universal quantum computing systems with the eventual goal of full fault tolerance.

- However, we believe “Quantum Advantage,” where we show significant improvement over classical methods and machines, may happen in the next decade, well before fault tolerance.

- Don’t say “quantum computing will.” Say it “might.” Publish your results and your measurements.

- Since May, 2016, IBM has hosted the IBM Q Experience, the most advanced and most widely used quantum cloud service. Over 100,000 users have executed close to 9 million quantum circuits. There is no charge for using the IBM Q Experience.

- Qiskit is the most advanced open source framework for programming a quantum computer. It has components that provide high level user libraries, low level access, APIs for connecting to quantum computers and simulators, and new measurement tools for errors and performance.

- Chemistry, AI, and cross-industry techniques such as Monte Carlo replacements are the areas that show great promise for the earliest Quantum Advantage examples.

- The IBM Q Network is built around a worldwide collection of hubs, direct partnerships, academic memberships, and startups working accelerate educations and to find the earliest use cases that demonstrate Quantum Advantage.

- Last week IBM Q published “Cramming More Power Into a Quantum Device” that discussed the whole-system Quantum Volume measurement, how we have doubled this every year since 2017, and how we believe there is headroom to continue at this pace.

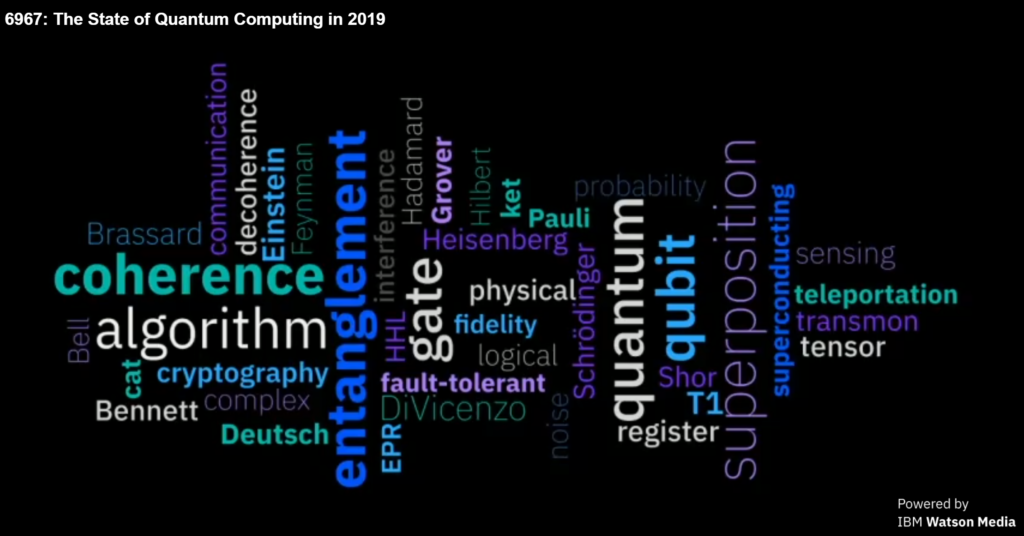

Talk: The state of quantum computing in 2019

Here’s a video of the session that my IBM Q colleague Anthony J. Annunziata and I led at IBM Think in San Francisco a couple of weeks ago.

If I seem slightly breathless, I was. I had about 4 minutes to get from a client meeting in Moscone North to the speaking venue in Moscone South.

Click on the image to go to the video.

Talking about quantum computing and the IBM Q System One

Here’s a video I filmed with Fortune about some of the basic principles of quantum computing and the IBM Q System One announcement.

Hello again

After 15 years of blogging and posting at several sites including IBM’s and my own sutor.com, I’ve started a new site and blog to complement the other postings.

After 15 years of blogging and posting at several sites including IBM’s and my own sutor.com, I’ve started a new site and blog to complement the other postings.

I give a lot of talks, write a variety of things, am featured in videos with my colleagues, and work as a tech exec during my day job. I’m going to use this to highlight what I’m up to with the first three of these. For confidentiality reasons I can’t talk much about my primary work until it bubbles out and is ready for public announcement and discussion.

Stay tuned because it’s going to be a busy 2019!

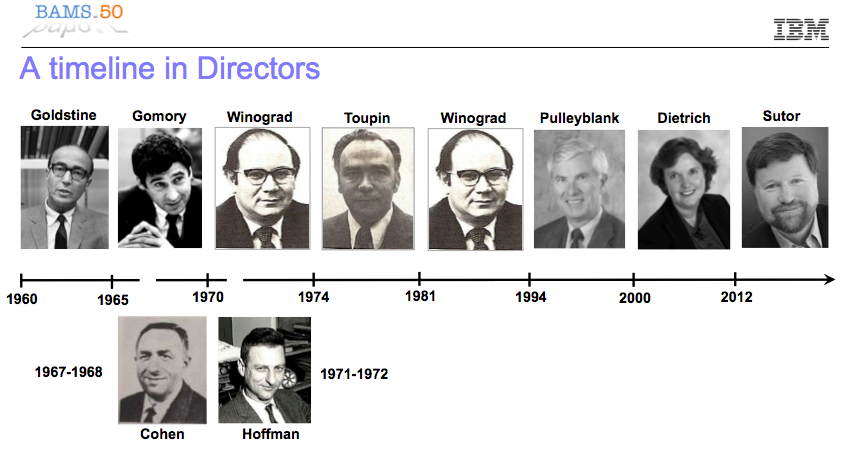

Math and Analytics at IBM Research: 50+ Years

I set about lining up volunteers to organize the anniversary events for the year and sent an email to our 300 worldwide members of what is now called the Business Analytics and Mathematical Sciences strategy area. Not long afterwards, I received a note from Alan Hoffman, a former director of the department, saying that he was pretty sure that the department had been around since 1958 or 59. So our 50th Anniversary became the 50+ Anniversary. Evidently mathematicians know the theory of arithmetic but don’t always practice it correctly

The first director of the department was Herman Goldstine who joined after working on the ENIAC computer and a stint at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Goldstine is pictured in the first photo on the right at a reception at the T.J. Watson Research Center in the early 1960s. Goldstine died in 2004, but all other directors of the department are still alive.

We decided that the first event of the year celebrating the (more than) half century of the department would be a reunion of the directors for a morning of panel discussions. This took place this last Wednesday, May 1, 2013.

I started the day by giving a glimpse of what the department looks like today: the above-mentioned 300 Ph.D.s, software engineers, postdocs, and other staff distributed over the areas of optimization, analytics, visual analytics, and social business in 10 of IBM’s 12 global labs.

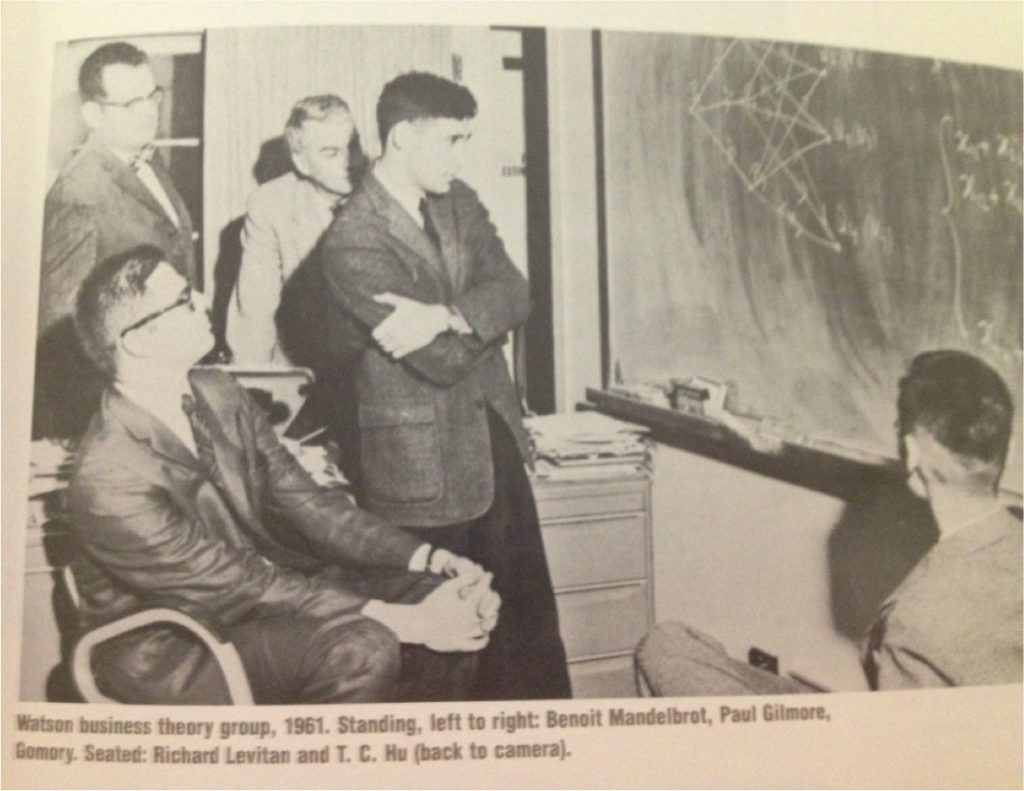

I then introduced our panel pictured in the photo above. From left to right we have me, Brenda Dietrich, Bill Pulleyblank, Shmuel Winograd, Roy Adler (a mathematician who was in the department during the tenures of all the other directors except me), Alan Hoffman, Dick Toupin, Hirsh Cohen, and Ralph Gomory.

My goal for the discussion was to go back and look at some of the history and culture of the math department over the last five decades. I was hoping we would hear anecdotes and stories of what life was like, the challenges they faced, and the major successes and disappointments.

Other than a few questions I had prepared, I wasn’t sure where our conversation would go. The many researchers who joined us in the auditorium at the T. J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, NY, or via the video feed going out to the other worldwide labs would have a chance to ask questions near the end of the morning.

I’m not going to go over every question and answer but rather give you the gist of what we spoke about.

- Ralph Gomory reminded us that the department was started in a much different time, during the Cold War. The problems they were trying to solve using the hardware and the software of the day were often related highly confidential. However, every era of the department has had its own focus, burning problems to be solved, and operational environment.

- Hirsh Cohen got his inspiration for the mathematics he did by solving practical problems such as those related to the large mainframe-connected printers. Many people feel that mathematics shouldn’t stray too far from the concrete, but it is not that simple. This isn’t just applied mathematics, it is a way of looking for inspiration that may express itself in more theoretical ways. The panelists mentioned more than once that the original posers of business or engineering problems might not recognize the mathematics that was developed in response. (I think there is nothing wrong with theoretical mathematics with no direct connection to the physical world, but there are some areas of mathematical pursuit that I think are just silly and of marginal pure or applied interest.)

- In response to my question about balancing business needs with the desire to advance basic science, Shmuel Winograd told me I had asked the wrong question: it was about the integration of business with basic science, not a partitioning of time or resources between them. This very much sets the tone of how you manage such a science organization in a commercial company. The successful integration of these concerns may also be why IBM Research is pretty much the sole survivor of the industrial research labs from the 1950s and 1960s.

- There was general consensus that it is difficult to get a researcher to do science in an area that he or she fundamentally does not want to work. This was redirected to the audience members who were reminded to understand what they loved to do and then find a way to do it. (This sounded like a bit of a management challenge to me, and I suspect I’ll hear about it again.)

- Time gives a great perspective on the quality and significance of scientific work that is just not obvious while you are the middle of it. This is one of the reasons why retrospectives such as this can be so satisfying.

After the first panel and coffee break, we came back and I started the session looking at the future of the department instead of the history. We have an internal department social network community in IBM Connections and I started by summarizing some of the suggestions people came up with about what we’ll be doing in the department in five, ten, and twenty years.

Sustainability, robotic applications of cognitive computing, and mathematical algorithms for quantum computing were all suggested. Note that his was all fun speculation, not strategy development!

Eleni Pratsini, Director of Optimization Research, and Chid Apte, Director of Analytics Research, then each discussed technical topics that could be future areas for scientific research as well as having significant business use.

After the final Q&A session, we got everyone on stage for a group photo.

One thing that struck me when we were doing the research through the archives was how much more of a record we have of the first decade of the department than we do of the 40+ years afterwards. In those early days, each department did a typed report of its activities which was then sent to management and archived.

With the increasing use of email and, much later, digital photos, we just don’t have easy if any access to what happened month by month. As part of this 50+ Anniversary, I’m going to organize an effort to do a better job of finding and cataloging the documents, photos, and video of the department.

This should make it easier for future celebrations of the department’s history. I suspect I’m not going to make it to the 100th anniversary, but I just might get to the 75th. For the record for those who come after me, that will be in 2034.